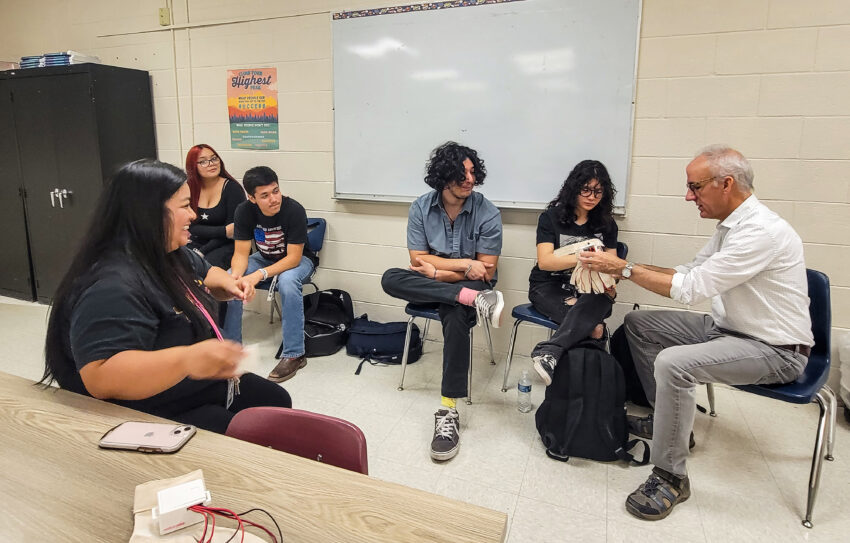

MESA Students with Dr. Steve Cox. Courtesy.NNMC

ESPAÑOLA — Students from Northern New Mexico College’s (NNMC) engineering program and Española Valley High School’s (EVHS) Math, Engineering, Science Achievement (MESA) program are applying engineering skills they are studying to a project that could significantly improve the lives of Parkinson’s patients.

Under the direction and mentorship of Dr. Steve Cox, Associate Professor/Engineering Technology at NNMC, and Española Valley High teachers Janice Badongen Patal-e and Lyne Salero, the students are designing a glove that applies small brief vibrations to the fingertips to alleviate symptoms of the disease.

“I like the fact that this has the potential to improve someone’s life. It’s not just trying to achieve a grade,” said Anita DeAguero, one of two Northern students involved in the project. “It just makes it more exciting, and it makes you enjoy the work you’re doing a lot more.”

Both DeAguero and Jafett Garcia, her partner on the project, have earned Associate of Engineering in Pre-Engineering degrees from Northern and are pursuing their Bachelor in Engineering of Electromechanical Engineering Technology. Both are currently interns at Los Alamos National Laboratory and are considering pursuing careers at LANL after graduation.

Creating a Community and Educational Connection

Minna Santos, whose husband Brandon was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease in 2014, suggested the project to Cox. Brandon had reached the highest dosage of his medication while his symptoms continued to worsen. Minna saw a story on the Today Show about researchers at Stanford Medicine creating a Parkinson’s glove that reduced symptoms such as freezing gait and tremors (https://www.today.com/video/new-vibrating-glove-eliminates-parkinson-s-tremor-157390405854). If further testing confirmed the results, researchers anticipated the glove would be on the market in two years.

“I was hoping we could come up with a very affordable intervention for the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, because I’m sure once this does come out on the market, it’s going to be very expensive,” Minna said.

For Cox, this was a study project with practical applications and an opportunity to connect his NNMC engineering students with the MESA students he regularly works with. Garcia was already assisting Cox in that effort, and he and DeAguero both mentored the MESA students throughout the project.

The Parkinson’s glove designed by Dr. Peter Tass and his team at Stanford Medicine stimulates the fingers with a random pattern of vibrations, which resets nerve cells that misfire in the brains of Parkinson’s patients. Twenty patients who participated in the first trial all showed improvement, some of it remarkable. The students set out to reverse engineer the glove created by Stanford.

“We took the Stanford research and converted that research into code, and the code is the magic,” Garcia said, “It’s helping us to create the patterns and shuffles and necessary bursts that we need for the patient to have these mechanical vibrations through small DC motors.”

The major challenges were writing code to create vibro-tactile vibrations to stimulate the nerves in the right frequencies and sequences, using a 3-D printer to build a wearable container for the circuit boards and creating a glove to hold the wiring to the fingertips that could be worn comfortably for two hours at a time (the duration for maximum benefit), which Cox called “a full-blown manufacturing problem.”

“This combination of hardware, software and manufacturing is a big deal. We typically put them in silos: you learn about each of those, but it’s not until you get out into the real world that you realize this all has to come together if you’re going to make a product,” Cox said. “So making a product that integrates these three silos is a huge learning opportunity for our students. Those are life skills that will help all of them in their journey.”

The teams created several prototypes, working to make the gloves more comfortable, more ergonomic and more efficient. The first microcontroller prototype was relatively large, requiring the patient to sit in a chair for the entire treatment. To make the gloves portable, they purchased and programmed an ATtiny 85, a microcontroller small enough to fit into a casing about the size of a smart watch. The prototype the teams developed could be produced for about $25.

“It was not easy. We struggled trying to change it from that big thing to the little microcontroller,” Garcia said. “It is a process, and you have to be positive and persistent.”

The MESA connection

MESA students Chelsea Sisneros, Dafne Rodriguez, Angel Zavala and Emilio Samaniego had more personal involvement with Minna and Brandon. Cox suggested this project for entry into the MESA U.S.A. competition, which had to address eliminating inequity thru human-centered engineering design. Minna shared information about Brandon’s situation with the students, who were eager to make a glove he could wear comfortably either sitting or standing, since sitting for long periods was difficult for him. They developed multiple versions based on Brandon’s feedback, striving to make the glove more user-friendly.

“One thing I thought was really cool about the project is that it informed the kids about a real problem in the world and it put a face on it. It’s good to have kids challenged with a real problem that makes a difference,” Minna Santos said.

“I think it gave more inspiration to the students,” said Badongen Patal-e, mathematics teacher at EVHS. “I’m very proud of them taking on the challenge. They could have just brushed it off, saying, that is not what we came for in this class. But they were committed to do it.”

The class met with Brandon several times via Zoom, and even measured his hand using the platform. When Cox delivered the first of several prototypes to Brandon July 15, 2023, his gratitude was evident. The students’ understanding of Brandon’s needs, especially in terms of getting the glove on and off by himself, greatly increased when Brandon was eventually able to meet with them in person.

“The high school students had an amazing relationship with Brandon,” Cox said. “Clearly these kids have spent a lot of time with elders in their family. They were so gentle and patient and understanding, working really hard to make sure that they understood the quality-of-life issues affecting Brandon. That empathy led to changes in his symptoms.”

After the students’ first Zoom meeting with Brandon, he was so energized he asked Minna to take him to Santa Fe for lunch. Not only was that a rare request, he read a magazine during the trip. He had not read anything for a couple years. “I think it was really inspiring to him to have someone interested in his problem and trying to solve it,” Minna said.

The students’ commitment to the project was evident as they displayed their various prototypes and talked about working with Brandon and the thrill of seeing the coding they were learning put to practical use.

“Imagine that you can’t do anything independently, you need help to even walk to the bathroom,” Chelsea Sisneros said. “There’s a lot of people we could help. I know a couple people as well. It really makes you think how it would be for you to be in that position.”

“It started as just a class and then it turned into a real thing. We just kept going on with it and it got more and more interesting,” Dafne Rodriguez said. “It felt good knowing that what we’re doing can help a real person, instead of just being one of those little projects that you forget about in a week.”

Brandon reported that his tremors decreased after just a few days of wearing the glove, but the severity of his disease prevented him from consistently wearing the device two hours a day, limiting his progress.

Badongen Patal-e and Salero were instrumental in the project’s success. The students had high praise for them, not only for their help on the Parkinson’s glove but for pushing them to excel academically on every level and using their own money to buy classroom supplies.

“The teachers did an amazing amount of work helping me mentor these students,” Cox said.

Steady Hands Wins in Competition

The students won 1st place for their design brief in the statewide 2023 MESA competition (https://www.nmmesa.org/), and 2nd place for academic poster, prototype pitch, technical interview and overall project. Their high scores in competition against a half dozen other schools (some with multiple teams) are especially impressive considering this was the first time any of them had competed and they were sleep deprived for their presentation. Their prototype stopped working the night before, so instead of rehearsing the team ran to Walmart to buy parts and worked until 3 a.m. to repair it.

In 2024, the original team, joined by Jeremy Vigil, Juan Andres Maestas, Jordan Martinez, Dylan Sandoval, Matthew Abeyta Jr. and Silvy Talamante Baca, went on to win one of the coveted New Mexico Governor’s STEM Challenge awards (https://newmexicostem.org/). In this competition, Industry Sponsors judge teams, with each company choosing their top team. Arcadis sponsored the EVHS STEM Team’s “Steady Hands” project, praising their research-based technical knowledge, methodologies for product development, testing, documentation and multiple iterations of product improvement. They also commended the students for their teamwork, each member’s investment in and deep understanding of the project and the empathy they brought to it.

“We love that someone in the local community came to these students with a complex problem, a very personal problem, one that is not easy to solve – and the students chose to accept this challenge as their own. They embraced Mr. and Mrs. Santos in their hearts and the real suffering associated with Parkinson’s disease…They literally followed the full product development process until they had created the gloves Mr. and Mrs. Santos could previously only wish for. They created access to medical technology and improved quality of life! The Steady Hands project demonstrates the power of designing with empathy.”

Deployment of the Prototype

For these students, developing the glove was more about helping Brandon and other community members than winning awards. Most of the original team has been working with Cox, DeAguero and Garcia to improve and develop 10 more prototypes of the glove, made possible by support by STEM Santa Fe and the Encantado Foundation. Cox is working to get approval from Northern’s Institutional Review Board to deploy those gloves in the community. He is also seeking grant funding to continue improving the glove, including further miniaturization and wi-fi capabilities.

“Our vision is not to make a profit. It is to help people, to help the community, to actually help others that cannot afford expensive devices for Parkinson’s disease,” Garcia said.

“I’m glad because these kids made it more than a competition, that they are not giving up,” Badongen Patal-e said. “Even though the competition is finished, they’re like still here, willing to help. So I’m challenging the students to do more, to improve more, and maybe join more competitions as a part of information dissemination.”

Cox has two hopes from the Parkinson’s glove project. One is to design an effective and affordable glove for the community. The other is that this type of project will encourage the students involved to continue their STEM education at Northern.

“I’m super proud of Northern, but unless we build projects with the high school, we’re going to remain an empty vessel. Jafett and Anita are the entire class,” Cox said. “So we need to change that pipeline. My bigger goal is renewing conversations with the high school, making Northern a relevant place.”